Tropical climate variability Germany visit

Science and autumn in Germany

After many years, it was so nice to be back in Germany the first time again during Autumn. I forgot how beautiful and golden this season presents in Germany with the smell of freshly fallen leaves everywhere. Many childhood memories running through mountains of leaves and collecting chestnuts for the animals. Golden leaves, crips mornings and admittedly I could have skipped the time to wait for the low lying “graune Suppe” of clouds to disappear during the course of the day. But even those grey days add the cosy feeling you only get during German autumn.

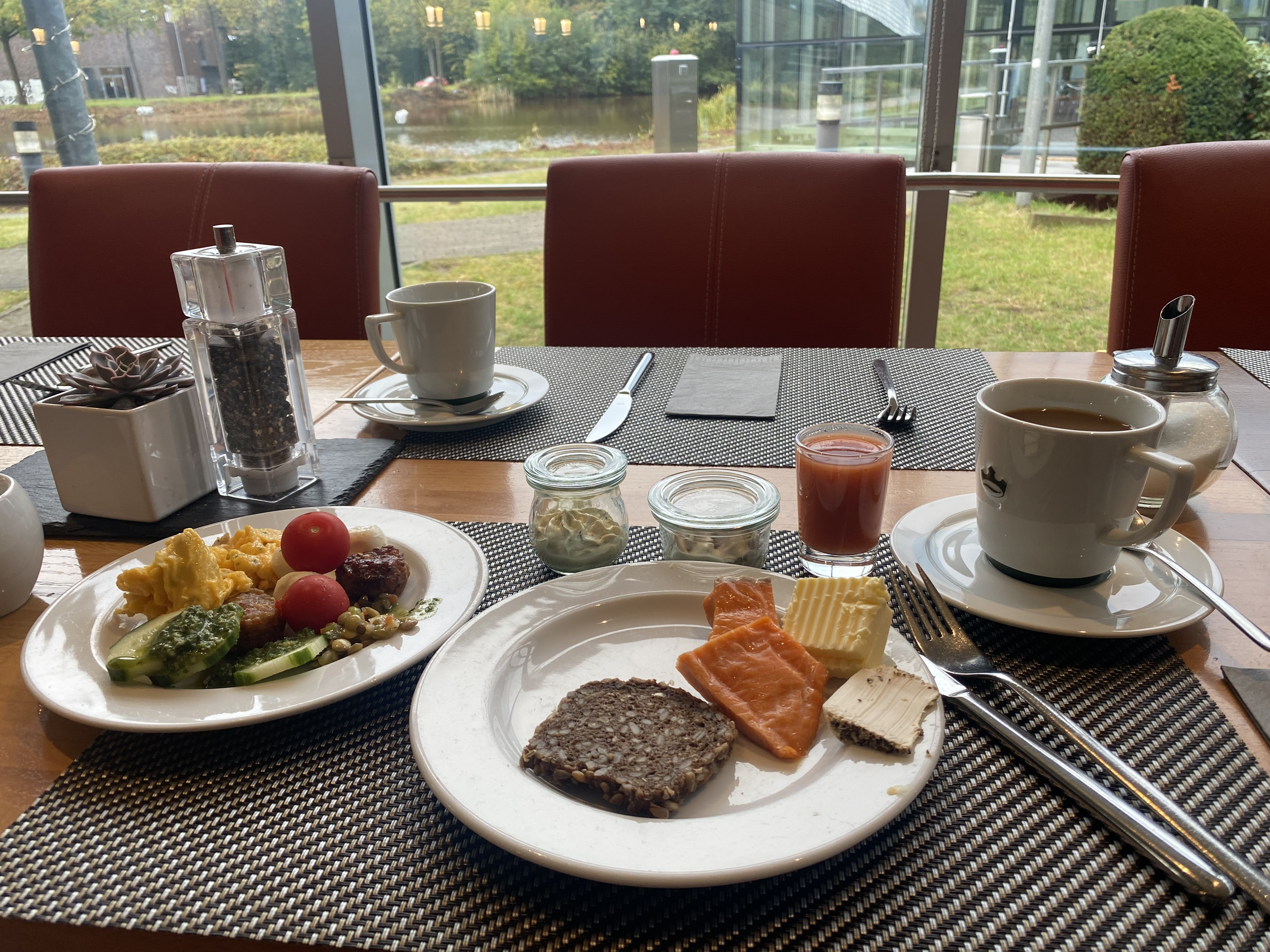

My trip started in Bremen for the SPP2299 meeting—a DFG priority program on tropical climate variability and coral reefs. The meeting was held near a fantastic science museum called Universum Bremen. I was impressed by the hands-on experiments and the tight involvement and collaboration with German universities and research institutions which brings this science museum very close to cutting edge of research.

SPP2299 Highlights

The SPP meeting in Bremen on tropical climate variability and coral reefs was incredible and packed with interesting people and talks. I can’t possibly easily summarise the incredible amount of research done in this area. But a few things stuck with me, and I am excited to so many things coming out soon. An example is how coral records can exaggerate past decadal variability compared to gridded SST datasets (Dolman & Laepple, 2025 [Dolman, A. M., & Laepple, T. (2025). Temperature variability on coral reefs versus Gridded SST – The long and the short of it. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, 26, e2025GC012351. ]). The paper suggests that coral records reflect very localised temperature fluctuations, while gridded SST products provide a larger, averaged view of the ocean. The difference in variability is mainly attributed to this difference in spatial scale, rather than other potential influences on the temperature data. The study used in-situ temperature loggers on coral reefs to help isolate the effects of spatial scale from other non-climatic factors that can influence coral temperature reading. Another highlight was work on volcanic cooling and freshening in the Indian Ocean during the early 19th century by Hana Camelia Marum. Looking forward seeing this out.

After Bremen, I took the train to Hamburg for research visits at MPI and DKRZ. Traveling by train felt like a novelty after years in Australia. It’s such a nice way of traveling even though delays are part of the game, certainly for the Deutsche Bahn…

Hamburg is a beautiful city and somewhat a hot spot for climate related research. With the Max Planck Institute of Meteorology and the Deutschen Klima Rechenzentrum certainly leading role in German and international research. I had great discussions focused on how we can utilise artificial intelligence in atmospheric science. While challenging, it seems to offer short cuts which usually require immense resources. For example, we are often interested to quantify the range of natural or intrinsic climate variability. How much does rainfall vary over the years? Some years are really wet, some very dry but most often we see average rainfall. Often the observational records isn’t enough, a very dry year could be a very rare event that hasn’t been observed in our odd 80 years of reliable observations. Climate science often borrows climate simulations for those kinds of questions. Running a climate model once, gives you one realisation similar to our one and only Earth. But there are multiple pathways of alternative Earths possible which can provide us with a number of different possible realities that certain things in our climate system vary. Running climate simulations run over and over again with slightly different initial conditions can provide you with a range of variability but annoyingly it is computational very expensive. AI can help there creating large ensembles of climate simulations reasonable cheap as shown by Meuer et al 2025. (Latent Ensemble Generator (LatEnGen) -> Meuer, Johannes, et al. “Latent Diffusion and Spatio-Temporal Transformers Generate Large Ensemble Climate Simulations.” IEEE Transactions on Artificial Intelligence (2025).

Other great applications include the reconstructions of data sparse observational fields. Instrumental records only cover a fraction of Earth’s history—less than 30% of the surface had measurements before 1900. AI-based reconstructions have shown to be able to reconstruct these fields more accurately and can even help resolve uncertainties in for example early 19th century sea surface temperature trends (Addressing early 20th-century cold bias in ocean surface temperature observations (Sippel et al., 2024). Cutting edge AI can even be applied to past climate extremes like warm and cold days and nights (Plésiat et al., 2024) which is usually very hard. Observed extremes often suffer from spatial gaps and inaccuracies due to inadequate spatial extrapolation. AI can reconstruct past climate extremes of (warm and cold days and nights) and more e.g. TX90p and gridded extreme indices. Plésiat, É., Dunn, R.J.H., Donat, M.G. et al. Artificial intelligence reveals past climate extremes by reconstructing historical records. Nat Commun 15, 9191 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53464-2. These AI techniques can even help to discover past volcanic eruptions. Linking specific events e.g. past volcanic eruptions with its origin via AI -> Meuer, Johannes & Timmreck, Claudia & Fang, Shih-Wei & Kadow, Christopher. (2024). Fingerprints of past volcanic eruptions can be detected in historical climate records using machine learning. Communications Earth & Environment. 5. 10.1038/s43247-024-01617-y.

Overall, this ties well in with ongoing work on ENSO diversity and transitions, where understanding how events evolve and shift between states is key for improving predictions. Using Markov chain approaches (Freund et al., 2024) highlight how ENSO behaviour has changed over time and how models project future transitions. Combining these statistical frameworks with AI-driven reconstructions could open new doors for exploring ENSO complexity in both past and future climates. Instrumental data, especially in the tropical Pacific, are imperfect and often insufficient for studying pre-industrial ENSO. Future work utilising these AI advances could shed new light on long-term warming patterns and diverse ENSO events using AI-driven reconstructions. So there is plenty of scope for collaboration on topics like AI-based climate science, reconstructions. For now, it’s back home with lots of ideas and a renewed appreciation for how science, Germany, and a few golden leaves can make for a memorable journey.